Introduction

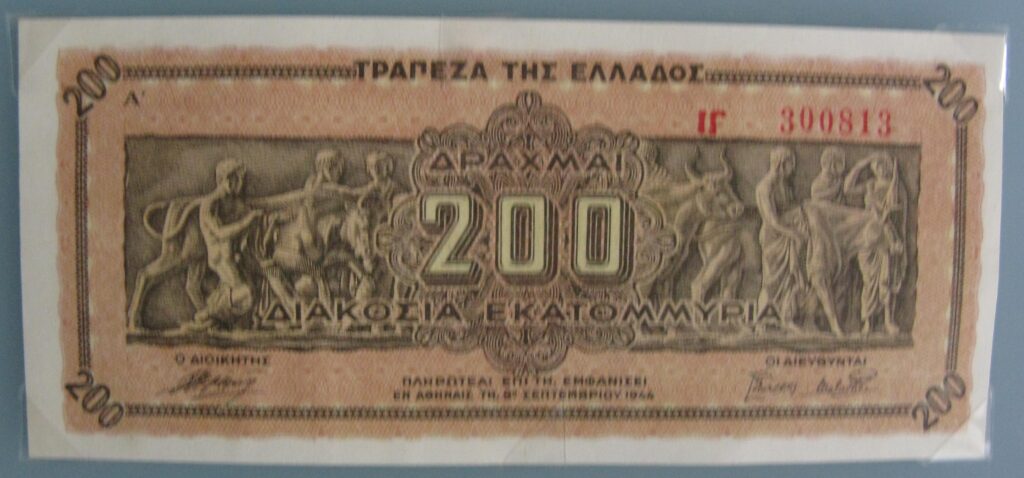

Exploitation of raw materials, forced labor, and economic control always played a role in expanding the German sphere of influence in Europe. Southeastern Europe was particularly important in this regard, especially since the Aegean islands and Crete were of strategic significance for controlling the eastern Mediterranean.

German elite circles in politics, the economy, and in the scientific field were also greatly interested in Greece’s ancient treasures. In the Third Reich, there was a strong emphasis on an alleged “Nordic” or “Aryan” origin narrative. Classical Greek antiquity was admired, and the Greater German Reich was meant to present itself as even more significant. The Nazi elite, including figures like Hitler, were highly interested in classical art and architecture, using them to project an image of the Third Reich as a successor to a “pure,” racially superior ancient past. Greek antiquity was selectively appropriated to support the regime’s racial theories, focusing on an alleged shared “Aryan” origin narrative that glorified a militaristic society (e.g., the Spartans). This narrative was in stark contrast to their contemporary view of modern Greeks, whom many Nazis viewed as racially inferior (a “cautionary” tale of “mixing” with Slavic peoples).

Invasion

The German invasion of Crete began with the Battle of Crete (Operation “Mercury”) – a large-scale airborne assault with paratroopers and gliders from 20 May to 1 June 1941. After the invasion, Greece was divided into three occupation zones: German, Italian, and Bulgarian. The German zone, which included strategically vital areas like Athens, Thessaloniki, and most of Crete, was administered by the Wehrmacht (German military) under a commander-in-chief. A collaborationist puppet government, known as the “Greek State,” was installed but held no real power: The occupation was marked by severe famine, mass executions, and widespread destruction. The primary German interest was strategic control of the Eastern Mediterranean and economic plunder to support their war effort.

Occupation of Crete

The invasion, launched on May 20, 1941, was the first large-scale airborne assault in military history. German paratroopers targeted key airfields on the north coast, meeting fierce resistance from Allied forces (British, Australian, New Zealand, and Greek troops) and Cretan civilians, who often fought with makeshift weapons. The conquest took several days, and the Germans gained full control of the island by early June 1941. Though the Germans eventually captured the island by June 1, they suffered heavy casualties, leading Adolf Hitler to abandon further large-scale airborne operations for the rest of the war, calling Crete “the graveyard of the German paratroopers”

Retaliation and Reprisals for the Cretan Resistance

The order for retaliation included instructions such as “executions,” “burning of villages,” and “extermination of the male population of entire areas.”

The German army did not tolerate any resistance to its aggression, as brutal retaliation would follow. However, the Greek army and the civilian population showed courageous resistance, defending their country against the invaders. After the Germans occupied Crete, they carried out systematic and brutal retaliatory measures. Historical reports emphasize that these reprisals were executed mercilessly, without regard for age or gender. Following the killings, villages were completely destroyed, livestock was killed, and supplies were plundered. This approach – a combination of direct killing, destruction, and psychological intimidation – was typical of German retaliation in other occupied territories in Europe as well.

On Crete itself, the Germans acted especially brutally; the German army carried out systematic massacres of the civilian population: several thousand people were killed in massacres, and villages such as Kandanos, Kondomari, and Alikianos were destroyed. It is estimated that around 3,474 inhabitants of Crete were killed through direct acts of violence during the German occupation from 1941 to 1945.

Key massacres and events in Crete

The German occupation was marked by violence, massacres, and systematic terror against the local population. Immediately following the end of the Battle of Crete, German General Kurt Student ordered a series of brutal reprisals against civilians for their role in the resistance.

Massacre of Kondomari (June 2, 1941)

German paratroopers executed the male population of the village of Kondomari. At least 23 men were killed in one of the first mass executions of civilians in occupied Europe.

Razing of Kandanos (June 3, 1941): In retaliation for the deaths of 25 German soldiers killed by local resistance fighters and civilians, the Germans massacred all 180 residents of Kandanos (men, women, and children) and completely razed the village to the ground.

Massacre of Alikianos

A series of executions took place in the area of Alikianos and nearby villages, with numerous men shot and villages burned in the days following the battle. Also on 2 June 1941, retaliatory measures were carried out against the civilian population of Alikianos and its surroundings. German paratroopers rounded up 42 male civilians from the village and led them to the church square in Alikianos, where they were shot in groups of about ten. According to reports, the victims were forced to dig their own graves beforehand, while their relatives—particularly women—were compelled to watch. Eyewitnesses also reported that valuables such as rings and watches were taken from the victims after the executions.

Later, on 1 August 1941, another wave of executions took place: 118 civilians from Alikianos and the surrounding villages were driven across the Keritis River, forced to dig graves, and shot.

On 3 June 1941, the village of Kandanos was destroyed. Approximately 180 villagers, including men, women, the elderly, and children, were murdered. All houses were then burned down, and the livestock was killed. The few survivors were expelled, and the site of the village was officially declared a “death zone”—a stark symbol of the brutality of the occupiers.

The Viannos Massacres (“Holocaust of Viannos”) (September 1943)

In retaliation for attacks on German occupation troops, over 500 civilians were killed, and villages were burned to the ground. This was one of the deadliest massacres during the German occupation of Greece, second only to the Massacre of Kalavryta on the mainland.

- Scale of the atrocity: Over three days, from September 14 – 16, 1943, Wehrmacht units launched a systematic extermination campaign against around 20 villages in the provinces of East Viannos and West Ierapetra.

- Victims: More than 500 civilians were executed, including men, women (some pregnant women were burned alive in houses), and children. All males over 16, and anyone arrested in the countryside regardless of age or gender, were ordered to be executed.

- Destruction: The villages were looted and burned, and all agricultural harvests were destroyed to ensure the survivors would not have food for the winter.

- Perpetrator: The operation was ordered by General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, who became known as “the Butcher of Crete” and was later executed for his war crimes after the war.

These massacres served as a brutal attempt to terrorize the local population into submission and deter them from supporting the resistance, but they ultimately failed to break the spirit of the Cretan people. German forces remained in control of the island until the very end of the war, finally surrendering to the Allies in May 1945, after Germany’s general surrender on the mainland in October 1944.

One of the most famous acts of the resistance was the 1944 kidnapping of the German commander of Crete, General Heinrich Kreipe, by a joint British SOE and Cretan resistance team.

Willi Siller was drafted into the Wehrmacht on 1 March 1941. His military career is documented in his denazification file (Source: Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, G.L.A. 465 q No. 367). As a member of the Wehrmacht, he was deployed in Poland and Russia in 1941. He never spoke about this period; only the denazification file provides information about it. However, he often recounted his later military service with enthusiasm, particularly his time on Crete. In 1942, Willi was briefly deployed in Sicily, and from 1942 to 1944 he served on Crete.

Source: https://www.weststadt-heidelberg-im-wandel.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/opa-willi-endfassung.pdf

After Poland*), the USSR, and Yugoslavia, Greece was among the countries most severely affected by German war crimes between 1942 and 1945. Around 80,000 to 100,000 civilians fell victim to massacres, forced labor, and famine blockades. There was a devastating famine in Greece during the early years of the occupation, caused by exploitation, plundering, and the economic collapse resulting from German control.

*) Poland was the country with the highest number of civilian deaths from German war crimes, estimated at 5 to 6 million people.

“In all the occupied territories I see the people living there stuffed full of food, while our own people are going hungry. For God´s sake, you haven’t been sent there to work for the well-big of the peoples entrusted to sou, but tonged hold of as much as you can so that the German people can live. I expect you to devote your energies to that. This continual concern for the allies must come then end once and for all. … I could not care less when you say that people under your administration are dying of hunger. let them perish so long as no German starves.”

Göring to reich Commissioners and Military Commanders of the occupied territories, 6 August 1942.

Source: M. Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44, page 9.

Sources:

M. Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44

https://www.gedenkorte-europa.eu

Futured Image: German soldiers hoisting the German War flag on Akropolis in Athens, Greece, Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-164-0389-23A / Theodor Scheerer / CC-BY-SA 3.0.