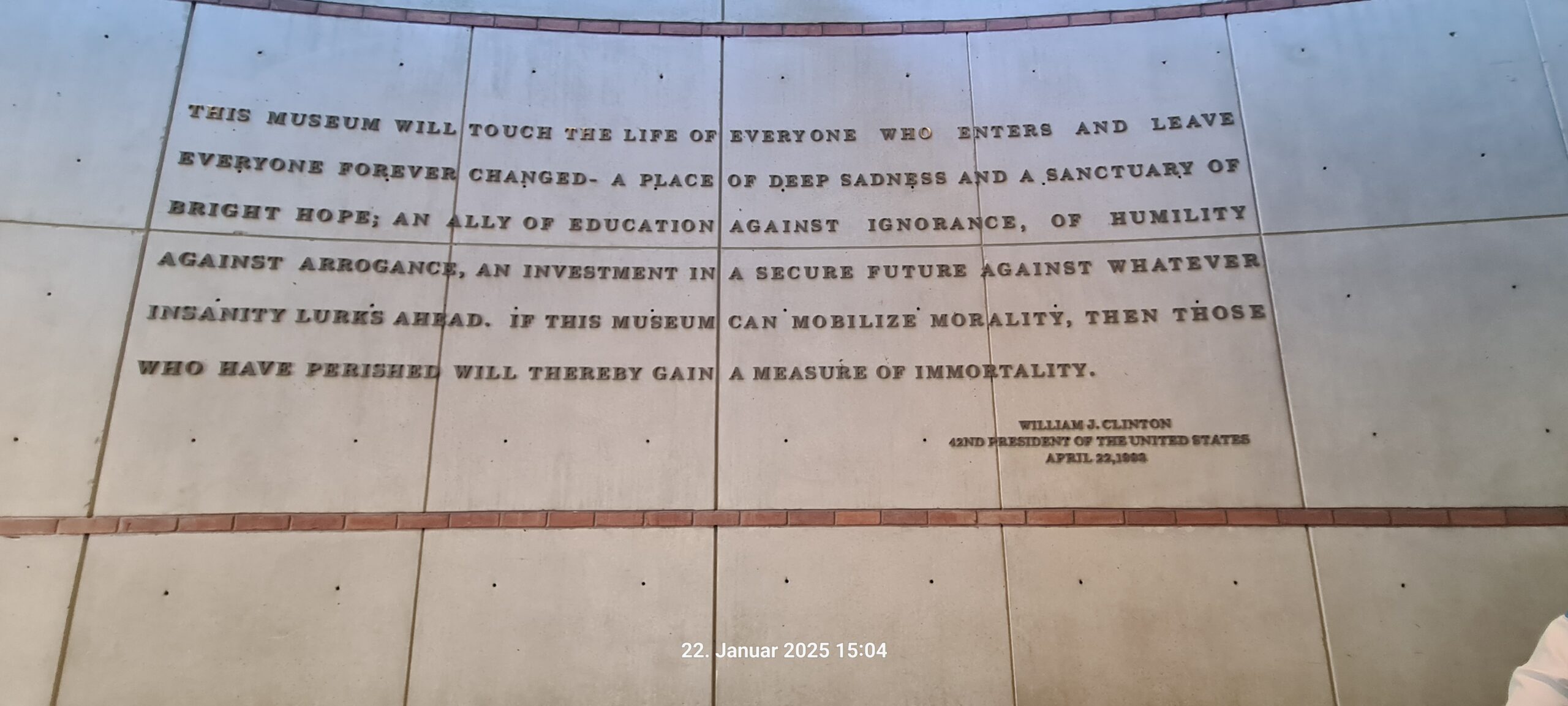

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. is located on the National Mall and serves as a living memorial to the Holocaust. Its mission is to inspire citizens and leaders around the world to confront hate, prevent genocide, and promote human dignity.

As of May 2025, this museum remains the most impressive Holocaust museum I have ever seen. It presents and teaches about the Holocaust in a deeply instructive and comprehensive way. The former German Nazi concentration and extermination camp complex, including Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, remains a powerful symbol of the Holocaust. While one may not be able to travel to Auschwitz to experience the site firsthand, this museum in Washington provides an extensive and profound understanding of what the Holocaust was and the horrors perpetrated by the Nazis. Like most museums in Washington, you can visit this memorial museum for free.

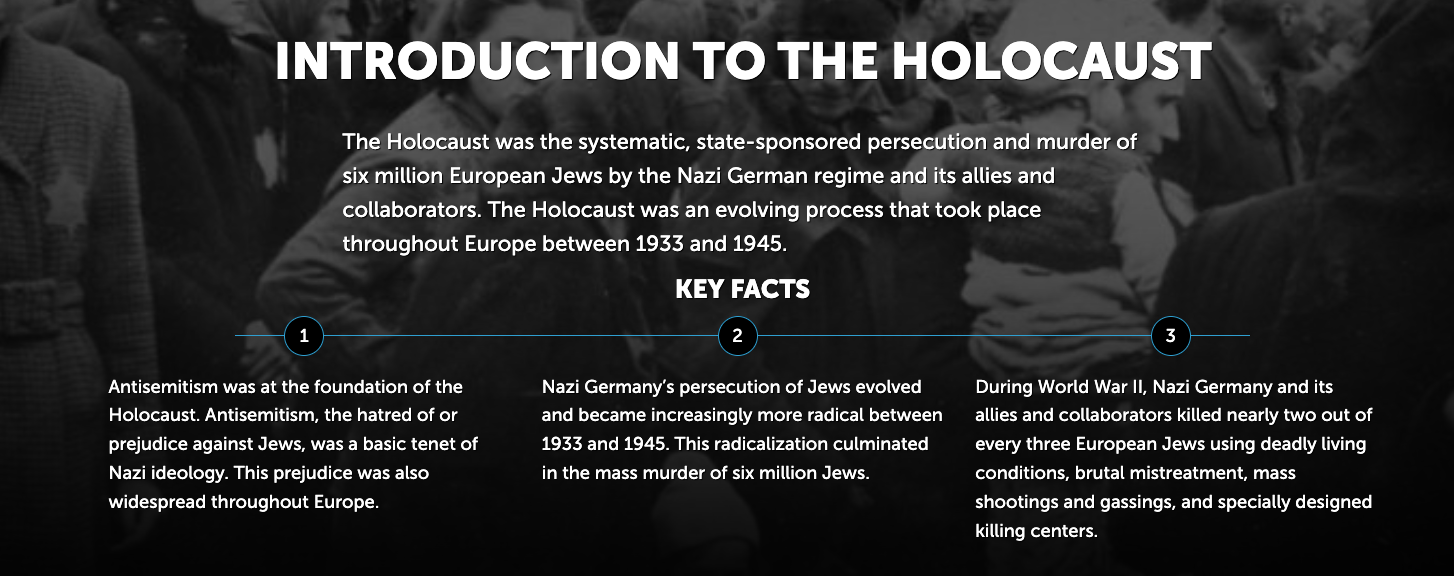

Holocaust?

The scope of the exhibits, the emotional depth, and the educational impact of the museum make it an unparalleled experience for understanding the horrors of the Holocaust.

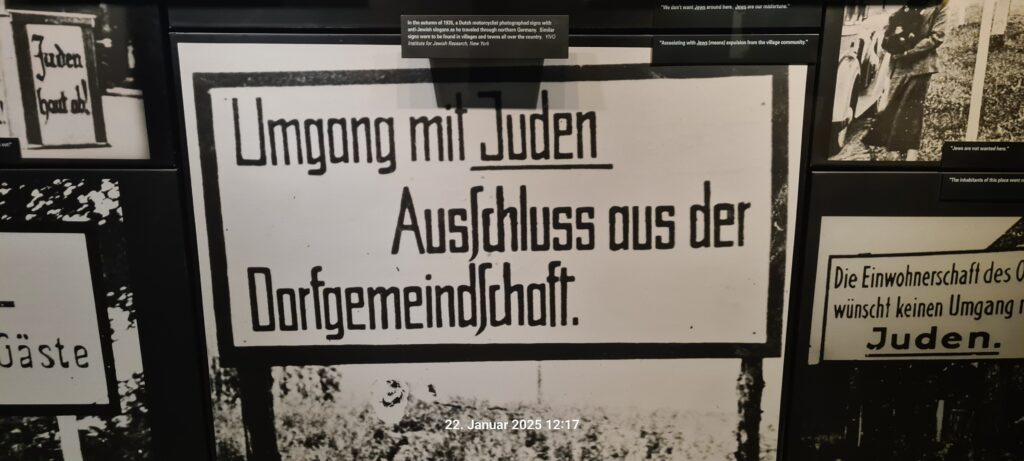

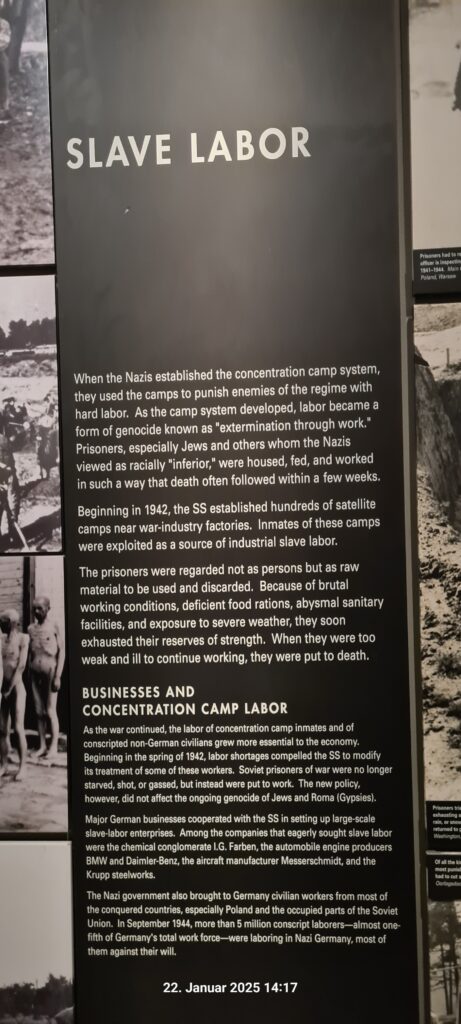

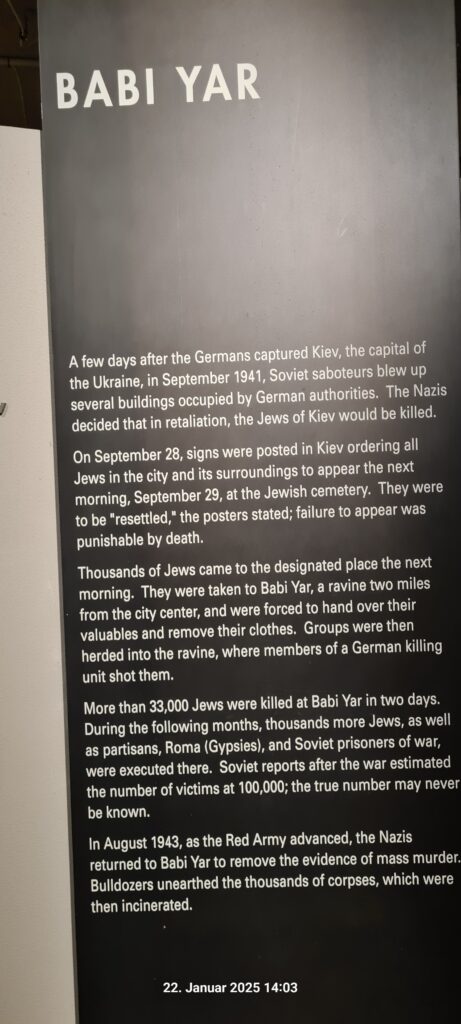

The museum offers a deeply emotional and educational experience, featuring powerful exhibits, historical documents, photographs, and personal testimonies that highlight the horrors of the Holocaust, while honoring the memory of its victims. The museum’s central exhibit, “The Holocaust,” tells the story of the rise of Nazi Germany, the implementation of the Final Solution, and the impact on European Jews and other marginalized groups.

The museum also conducts research, publishes educational resources, and advocates for human rights globally. Visitors can experience both permanent and rotating exhibits, attend lectures, and participate in various educational programs. It is a place of reflection, remembrance, and action against hatred and prejudice.

Reflections on That Past

We live in a modern age, the age of artificial intelligence, blockchain, and other advancements, and we often believe that such inhuman atrocities could never happen again. But we must not forget that, at the time when the Germans declared themselves the ‘superior race,’ they classified Poles as ‘subhuman’ and Jews as ‘inhuman.’ They invaded numerous countries in Europe, robbed them of their wealth, displaced and murdered civilians, and seized their homes. The survivors were forced to serve the ‘German race.’ At the time, Europe was ahead of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Germany had become a powerful, industrialized nation, with fields like psychology and sociology being formalized as sciences. Despite winning many Nobel Prizes and having a strong intellectual and cultural tradition, Germany’s experience with imperialism during its Second Reich had already involved the first mass killings of civilians (Genocid) which were under German Administration (colony) in Africa, the Herero and Namaqua genocide in German South West Africa (now Namibia), which took place from 1904 to 1907. The Herero people, followed by the Nama people, were subjected to brutal treatment by the German colonial forces, including mass killings, forced labor, and concentration camps. This event is widely regarded as the first genocide of the 20th century, predating the Holocaust by several decades. Then, with the rise of the Third Reich, they aimed to achieve what had been impossible for them with the Second Reich (Germany everywhere in the world, to make the world heal through the German spirit, etc.): to become even more dominant, willing to do anything necessary to achieve their so-called superiority.

What remains of it is the history, serving as a lesson for the entire world. The Third Reich and the Second Reich are not just Germany’s history – they are part of world history. The atrocities committed during these periods affected millions of people across Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

One such example is the traditionally strong bond of German descendants in Brazil with both the German Reichs (the Second and Third Reichs) and the German invasion of Brazilian maritime territory in 1942. German U-boats, operating in the Atlantic Ocean, directly targeted Brazilian merchant ships, military vessels, and civilian crews, often near the northeastern coast or close to Brazilian beaches. These ships, which were within Brazil’s territorial waters or just off the coast, were attacked without warning. These attacks were not confined to any ambiguous legal space; they were clear violations of international law and can rightfully be described as invasions of Brazilian maritime space. These U-boat strikes came from Germany, thousands of miles away, with the intent to kill and disrupt. Germany’s U-boat campaign against Brazil was not only an act of war but also an act of terror – terrorizing civilians, violating Brazil’s maritime sovereignty, and contributing to the broader horrors of World War II. Approximately 1,200 Brazilians were killed during Germany’s U-boat attacks on Brazilian ships within Brazil’s territorial waters between 1942 and 1943. At that time, Brazil and Germany were still business partners, but Germany turned against Brazil, using these attacks to weaken the country. Nazi sympathizers had a significant presence in southern Brazil, particularly in areas with large German immigrant populations, such as Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Rio Grande do Sul. These communities had maintained strong ties to Germany since the Second Reich (the German Empire), and many not only continued to speak German, attend German-language schools, and participate in cultural institutions that were linked to Germany, but they also avoided integration and assimilation into Brazilian society. Some even harbored plans to secede and create an independent German-speaking state (Neudeutschland), separate from Brazil. With the rise of the Third Reich, these German-descendant communities became increasingly sympathetic to Nazi ideology, and many of their business and cultural activities became closely tied to the Third Reich.

Public engagement with this history must be global and ongoing, not just for Germany’s sake but for the sake of understanding how these global histories are interwoven.